Hi-ya Baddies,

Welcome back! If you haven’t yet, please consider sharing this newsletter with your bird or bio-curious acquaintances. The more eyeballs we wrestle away from the algorithms, the better. Rebel on all fronts. Many thanks!

UPDATES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS

- Did you notice that our April writing on rat birth control scooped The Times by a few days? Yes, we’re prophetic and weird and sometimes stinky and (debatable) cool. We’re also working on organizing a rat birth control pilot in our very own hood. Stay tuned. From NYT’s post:

A new bill being introduced on Thursday would require the city’s health department to deploy salty pellets that sterilize both male and female rats as part of a pilot program. It would take place in two neighborhoods within so-called rat mitigation zones covering at least 10 city blocks.

There is another potential benefit: Contraceptives are not likely to harm wildlife like Flaco, the beloved Eurasian eagle-owl whose death was blamed in part on rat poison.

- Just a few US made oversized long-sleeve tees left. DM us. If you already did so, try again. We’re getting better organized by the day. Swear.

- ‘Member when we asked y’all readers to notice these curiously aesthetic’d brick puppies of eastern Greenpoint?

Well, besides it turning out that a few clubbies actually dwell(ed) in them, we got the word that two brothers—uncles of a current landlord who prefers to remain anonymous—built them in the early 2000’s. They are indeed crowned by Polish eagles, and “usually angels, for protection”. It is believed that the brick details were inspired by “ornate rugs”. Do you see ‘em? Until we learn more, look up when you’re strolling East Greenpoint, and bask in the glory of these strange palaces. More abound than you think.

- We’re doing another near-flung Walk on 5/19—this Sunday. Brooklyn Bridge Park — meet here — 9am. Just show up

- You may have noticed that this newsletter, while starting as an equally humble and ambitious monthly is—inspired by our obsession with Japanese micro-seasons— transmogrifying into a weekly. Those weeklies are feeling like our future. As for monthlies like this, we’ll experiment with long-form single topic essays that, sometimes more abstractly than others, are designed to free your nascent birder mind, sister-brother. In the meantime, don’t overthink it. Also don’t be surprised if we continue to tweak as we go <3

APRIL RECAP

- 72 bird species were noticed in McGolrick Park in April! Favorites & full list here.

- We did our free Saturday walk thing. Four times. Featuring—

Birds: White-throated Sparrow · Laughing Gull (flyover) · Yellow-bellied Sapsucker · Red-bellied Woodpecker · Red-tailed Hawk · Herring Gull (flyover) · Eastern Towhee · Hermit Thrush · Pine Warbler · Double-crested Cormorant (flyover) · Downy Woodpecker · American Crow · Black-and-white Warbler · Blue Jay · Common Grackle · Northern Cardinal · Northern Flicker · Ruby-crowned Kinglet · House Finch · Chipping Sparrow … And the virtually always present in urban parks like McGolrick: Rock Pigeon, European Starling, American Robin, House Sparrow, Mourning Dove

The Final Warbler Gauntlet! Maya! Stephen! Hayley! Madeline! Gimme! More! These hotties dizzled and dazzled through the names of the 22 warblers of McGolrick Park. All were sent away with prizes, our respect, and pretty heads cheep-full of reinitas. If you’re keen to similarly go all crazy diamond, don’t fret, there’ll be more opportunities to shine on.

- On Sunday, April 21 we walked Under the K Bridge with our buddies at North Brooklyn Parks Alliance. Highlight was a Belted Kingfisher—an improbable looking, rattling shorebird—and a subtly beautiful Swamp Sparrow. Also seen: American Kestrel · American Crow · Song Sparrow · White-throated Sparrow · Barn Swallow · American Robin · Canada Goose · Dark-eyed Junco · Hermit Thrush · Herring Gull · House Sparrow · Laughing Gull · Northern Mockingbird · Rock Pigeon

- The following Sunday, April 28 we visited Cooper Park. Highlights: Yellow-rumped Warbler • Common Raven • American Crow • Chipping Sparrow. Our sister space is small but mighty! It is also under-birded. If you live nearby, considering logging some species on eBird during your next visit.

The old crow vs. raven debacle, right? American Crows are much more common in NYC than Common Ravens. Get clear with this comic too

MBC SPOTIFY PLAYLIST — MAY

Here’s our approx. hour-long ode to May, courtesy of DJs Grackattax & RyFly a.k.a. DJ OverUnderhiser. Maybe use it like a classic-rock + ego-death palette-cleanse between the warbler calls you’re diligently committing to memory? And be sure to reference it while reading the below long-form by Julia.

MAY AT LENGTH

The Recommended Warbler: George Harrison Music to Raise the Consciousness By Julia Scinto

Here at McGolrick Bird Club, we caution against social media overuse for all the obvious reasons. I will not repeat the troubling stats and luddite mantras here; you all know them. But let’s be real: I’m no better than average Tech Age junkie. I use social media. A lot.

I know the root of my habit. Besides the fact that my Paleolithic era-wired emotions are being exploited by algorithmic overlords, there’s one feature that invariably keeps me boomeranging back to the platforms for more: the comments section.

I am a self-professed comment section miner. There’s gold in them there hills, you just have to pan a lot of fool’s stuff to find it. IMO: the comments section is the agora of the 21st Century—a digital age gathering place of ideas and unfiltered opinions from idiots and philosophers alike. And I’m here for it.

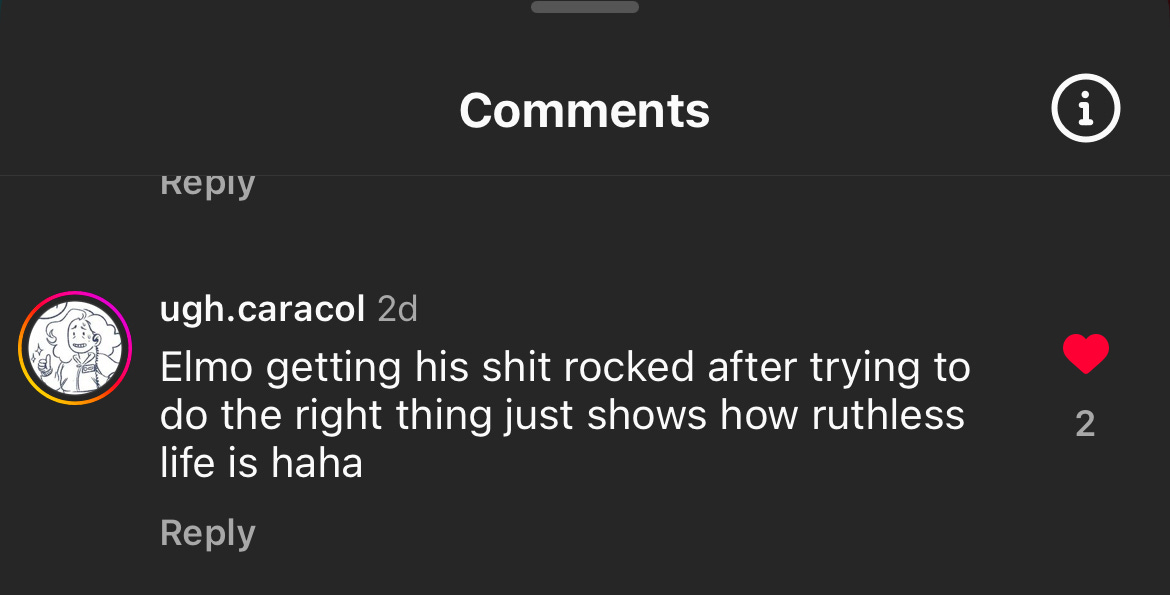

Example. If you’re at all familiar with February’s #Elmogate, you’ve probably watched “Larry David Attacks Elmo on Live TV”—TRIGGER WARNING: your first BFF is about to get choked in an episode of IRL Curb—and you’ll understand how the below comment sums up both the video and the overall experience of 2024:

Deeply dark humor appears in many a comments section. But insight and mystery has its place too.

Reader, this is why we are here today. I’m writing in attempt to synthesize several years of my own serpentine internal experience—ignited through music—that was profoundly summed up in a comment on a classic rock Instagram account by a stranger on the internet:

“That cat gave us more than just the music.”

The ‘cat’ (or, songbird, for our purposes) referred to above is George Harrison, and it is my pleasure to introduce him as The (very first) Recommended Warbler for this month’s theme: Music to Raise the Consciousness.

You may know George Harrison as the lead guitarist of The Beatles, or “the Quiet Beatle.” Along with bandmates John, Paul, & Ringo, George reached the height of international fame, material wealth, and public recognition in the 1960s and 70s.

”Beatlemania” rendered mostly female crowds so manic that the band couldn’t hear themselves play in live concerts over the frantic screaming. Security guards were overwhelmed; fans fainted, broke into hotel rooms, climbed into private room windows. The modern day equivalent would be akin to the combined forces of the Swifties, BeyHive, Beliebers and K-poppers all intensely fused into one obsessively devoted fandom.

The Beatles, despite being on top of the world, had to live as shut-ins. For safety and sanity reasons, they even stopped performing live in 1966, four years before the release of their final studio album. Suffice to say, even if you aren’t personally familiar with The Beatles’ body of work, your favorite musicians are. They’re legendary.

At first happy to ride the wave of the collaborative genius of John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s creative partnership, George’s contribution to The Beatles’ songwriting began as a slow trickle; one that would gradually became an integral part the band’s (and therefore the culture’s) electric downpour—washing the West of its sonic status quo. The new world he shaped is the one you, dear reader, have directly inherited. And it all happened, as these things do, “by accident.”

A ‘happy accident’? For those familiar with Beatles discography, you’ll notice their early 1960’s major key rock n’ roll melodies took a minor key, psychedelic turn with the approach of the 70s. This was mostly due to what George called “the dreaded lysergic.” LSD. Unwittingly consumed in coffee spiked* by dentist John Riley at a 1965 house party, George and John’s first trip was involuntary. That night, however, George tapped into consciousness for the first time.

*I have it on good authority from my dad (who experienced the far out, funky world of the late 60s and 70s) that this sort of thing “was pretty common in those days.”

Harrison’s contemporary, American psychologist-turned-spiritual teacher, Ram Dass, once asked his guru Neem Karoli Baba (“Maharajji”) to explain what LSD was. Keep in mind, before Ram Dass took up that moniker, he was born Richard Alpert. As Alpert, he was a highly respected Harvard psychology professor until he (along with his colleague Timothy Leary) was kicked out of said institution for conducting controlled experiments on students using psilocybin. Maharajji’s response: “LSD…is awakening the young folk in Kali Yuga. America is the most materialistic country…they wanted a material for approaching God, and they got it in the form of LSD.”

OBLIGATORY MBC PSA: “Psychedelics show a possibility,” Ram Dass synthesizes, “but beyond that you still have a lot of stuff to do.” Meaning, you can’t let the drugs do all the inner work for you. The same tools that George found to be his gateway to spirituality, would ultimately become gatekeepers to higher paths. As Ram Dass said about psychoanalysis—“you can only get as high as your therapist,”—George also said of spiritual enlightenment: “If you want to go higher, you have to stop getting high.”

It didn’t happen overnight for our Recommended Warbler. Life as a Beatle was beginning to wear on George; as money, fame, and the trappings of the material world ceased to satisfy a soul yearning for deeper meaning. “I just wanted someone to impress me,” George said in the mid-1960s, when meetings with superficiality-addled royalty and celebrities no longer amused.

In 1966, George met Ravi Shankar, an Indian classical sitar player and composer of Bengali origin. George was a decided fan and had experimented (admittedly clumsily) with the sitar on the 1965 track “Norwegian Wood” after being influenced by Ravi’s records.

Their meeting was life-altering for both parties. By the medium of music, according to Ravi, a devotee could connect with universal Oneness. Through dedication to his craft, and by following the Vedic principles of yoga-meditation and spiritual devotion, Ravi was a living example of a man in personal pursuit of God-consciousness. George was finally impressed. He studied the sitar under Ravi’s tutelage, and the two began a friendship and musical collaboration that endured throughout his life.

Ravi’s influence on George came at a pivotal time. Their friendship, often referred to as a father-son relationship (Ravi was 46 to George’s mere 23-years upon meeting), was one of mutual respect. Ravi’s gifting of the book “Autobiography of a Yogi” by Paramahansa Yogananda, and the months of sitar training in India among Ravi’s peers, were profoundly influential. George’s reluctant return to the London recording studio at the Beatles’ behest could no longer be separated from these newfound musical and philosophical understandings.

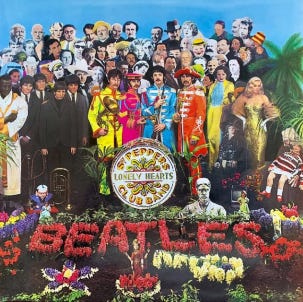

This transformation is most vividly witnessed in the song “Within You Without You,” composed by Harrison for the 1967 Beatles album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. In an album hailed as the cornerstone of British psychedelia, blending pop culture and high art into a mainstream format, Harrison’s track was the first exposure many in the West had to the Indian diaspora of Eastern sound, philosophy, and culture. The song is composed in the classical Indian form, as he was taught by his mentor, and includes three time signature changes. He is, notably (and surprisingly), the only Beatle to perform on the track, and recorded the traditional Indian instruments with London-based South Asian musicians, not the other Beatles members.

Listening to “Within You Without You” (found on MBC’s April ’24 Playlist) with this in mind, the reader is asked to rewind the clock half a century and imagine how ground-breaking this record must have been in 1967 England and America. For audiences accustomed to Elvis Presley, Mad Men-style advertisements, and news of the Vietnam War, imagine the shock of the lilting voice of George Harrison (The Quiet Beatle!) lyrically pontificating ancient Vedic meditations:

We were talking About the space between us all And the people Who hide themselves behind a wall of illusion Never glimpse the truth, then it's far too late When they pass away

Our true selves are separated by a wall of illusion. This illusion gets in the way of our love for one another. Free yourself from the illusion to recognize what is real: that we are all equal parts of a Universal One.

Later:

When you've seen beyond yourself Then you may find peace of mind is waiting there And the time will come when you see we're all one And life flows on within you and without you

The song’s instrumental interlude is a universe of sound: sitar, santoor, violins, and cellos, calling and responding to each other like morning birds confirming the previous night’s survival. And finally, at the song’s end, we hear George’s laugh, reminding us not to take this ultimate search for Oneness too seriously (he is from Liverpool, after all).

George also planted “clues to the spiritual aspect of me,” in the album’s iconic cover image. Look closely among the famous faces of Marilyn Monroe and Bob Dylan and you’ll find Self-Realization gurus from Paramahansa Yogananda’s yogic line of disciplic succession: Mahavatar Babaji, Lahiri Mahasaya, and Sri Yukteswar. Harrison’s request for Ghandi’s addition was denied by the British record label for being “too political.”

By the mid-60s, George had become synonymous with the devotees of the Hare Krishna movement—a monotheistic branch of the Hindu tradition that he would to practice (and financially support) all his life, despite receding from official affiliation in later years. In the late 60s, he formed a close association with the movement’s founder A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and was jokingly labeled within the movement as “a closet Krishna.” George was a devotee in all but name.

Spirituality had taken precedence in George’s life, more so than being a Beatle, and unfortunately eclipsing his relationship with his first wife, Patti Boyd. Patti would eventually leave George for his friend Eric Clapton, resulting in a highly-publicized divorce that the presiding attorney would later remark was the most amicable he’d ever seen. But not before George wrote what Frank Sinatra called “one of the most beautiful love songs ever written.” For whom it was written, however, is a matter of politic.

The 1969 single “Something,” (also on the MBC April ’24 playlist) from the Abbey Road album, is a Harrison composition seemingly written about his wife Patti. “Actually,” George confidentially told his devotee friends in London earlier that year, “it’s about Krishna. But I couldn’t say he, could I?” (Reader is reminded that in 1969, an English man singing a love song to a masculine recipient [deity or mortal] would have been beyond society’s understanding.) George would continue to blur the lines between romantic and divine love in his lyrics throughout his career, remarking that “Singing to the Lord or an individual is, in a way, the same. I’ve done that consciously in some songs.”

George’s sea change from mod rocker to mystic was tsunami-level, and not all Beatle fans wanted to brave the new waters. He had come to believe “there’s more to life than bogeying,” but working-class lads from Liverpool weren’t supposed to change, and he had evolved too much for many’s liking. The truth was, fame and fortune had changed George. He believed there was meaning in the personal act of change.

When, in 1970, the Beatles announced the band had broken-up, George was finally free to pursue a life outside the restrictions of the Fab Four. Later that year he would release the solo album, All Things Must Pass, to universal critical acclaim. But the album’s first hit song almost never was.

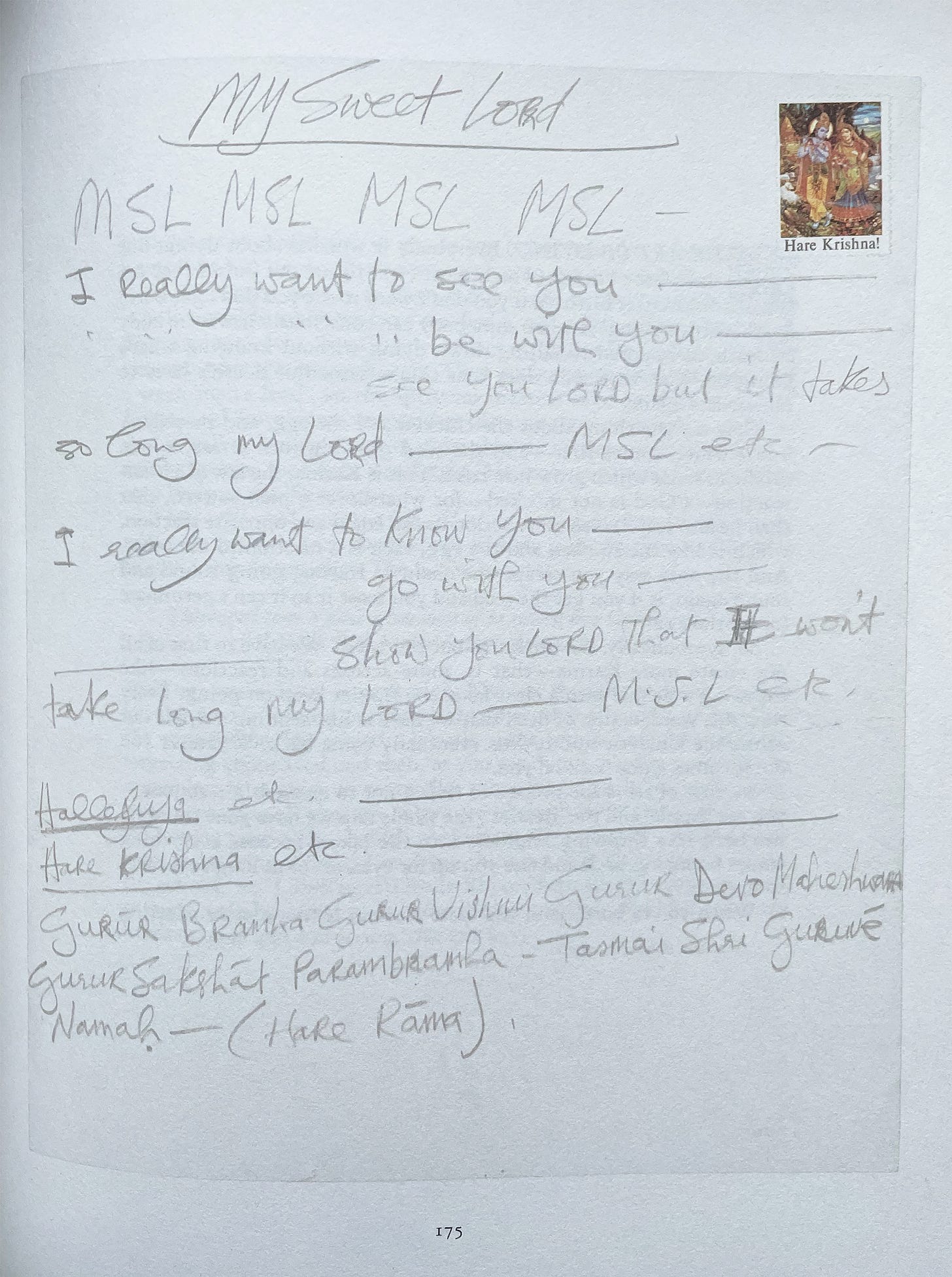

The biggest risk of George’s solo career was also a personal one: releasing the single “My Sweet Lord” (second track on the MBC April ’24 playlist). The song’s overtly religious themes were undeniable. “I thought a lot about whether to do 'My Sweet Lord’ or not, because I would be committing myself [to spirituality] publicly and I anticipated that a lot of people might get weird about it,” George confesses in his autobiography. “I was sticking my neck out on the chopping block because now I would have to live up to something, but at the same time I thought, ‘Nobody’s saying it; I wish somebody else was doing it.”

“My Sweet Lord” is a gospel-inspired devotional that speaks of the singer’s desire for connection with God through his personal expression of Krishna-Consciousness. The bird-conscious reader may note with interest that traditional depictions of Krishna feature the deity with an ornamental peacock feather in his crown. It is said the presence of all seven natural colors in the feather signifies that humans of all color ranges are of part of Krishna himself. The iridescent quality of these colors, according to Hindu philosophy, mimic the illusory nature of the physical world.

In the song, Harrison employs background singers to repeat “Hallelujah” in chorus only to intentionally replace the familiar Abrahamic expression with those of the Maha mantra (translated from the Sanskrit, to mean “great sacred chant”):

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare Hare Rama, Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare

In this way, Harrison discreetly instructs his audience to chant in the Eastern tradition without realizing it. “I don’t feel guilty or bad about it,” he admits, “in fact, it saved many a heroin addicts life.*”

“My Sweet Lord” was a hit despite initial trepidations, topping the charts internationally and becoming the UK’s biggest-selling single in 1971. The album itself established Harrison in the industry as a singer-songwriter in his own right and, arguably, as the strongest solo artist of the former Beatles members.

*Despite a subsequent copyright infringement suit (in which George was ruled to have unintentionally, yet “subconsciously copied” the song’s melody), his overall takeaway of the record remains that his motives behind its writing and its positive effects on the public have far exceeded the “legal hassle.”

“People always say I’m the Beatle who changed the most,” Harrison famously said. “But, really, that’s what I see life is about.” The process of change is often first acknowledged with accusations, not accolades. Yet, ironically, time teaches us that change (along with death and taxes) is one of life on Earth’s only reliable factors. For George, being changeable allowed him to transform from a quiet boy band member to a legendary guitarist, songwriter, and spiritualist on a mission of personal growth.

As migration season peaks, I’d like to remind the reader that pop idols aren’t the only ones being asked to face great changes in life. Our feathered friends, from the smallest Pine Warbler to the mighty Canada Goose face epic, many thousand mile journeys each spring and fall for the sheer sake of life-giving. (Think about that next time you toggle between “delivery” and “pick-up” on your food service app.) And yet, the result of these Herculean hardships is that we as birders revel with joy at their arrival to our humble parks and backyards. “Struggles,” Yogananda said, “are the nectar of life.” Without them, how else could we appreciate the beauty of their absence?

For us humans, self-realization is not as straight-forward as migrating. That thing called consciousness that George and John’s dentist inadvertently introduced them to requires more than a simple external change in environment to satisfy our souls’ desires. Unlike George and John, however, most of us won’t exceed all worldly standards of success by our mid-20s to fully understand this concept early in life (if at all). But “spiritual awakenings,” as the kids on TikTok call them, happen everyday.

If we are wise (or perhaps very lucky), we will learn that the battles we fight outside of ourselves can only be defeated once our inner demons have been vanquished. This is the path of yoga in the true Vedic tradition. Elevate your consciousness internally, Krishna instructs his devotee Arjuna in the Bhagavad-gītā?, and the external will follow. This is the road that George and his counter-culture contemporaries paved for us to tread; their influence now so deeply absorbed in our current reality we hardly seem to notice it.

That cat - excuse me, songbird - really did give us more than just the music. Do your Higher Self a favor and listen to George Harrison—the quiet, unsuspecting Beatle, whose personal transformation showed the West there was another way to do this dance called Life—and raise your Consciousness! He even dropped some far out tracks for you to move to while you do it. Go on, smash that ‘play’ button. Surrender to the sounds, and “Be Here Now.”

SOURCES & NOTES

Books

Here Comes The Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison By Joshua Greene

I, Me, Mine George Harrison autobiography By George Harrison and Derek Taylor

Remember Me & Fight By Pandava Bandhava Das

Documentaries

George Harrison: Living in the Material World Dir: Martin Scorsese HBO (2011)

Podcasts

Ram Dass Be Here And Now

Albums

Rubber Soul (1965) The Beatles

Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) The Beatles

Abbey Road (1969) The Beatles

All Things Must Pass (1970) George Harrison

Living in the Material World (1973) George Harrison

EPITAPH

Few birds are more beautiful than the Indigo Bunting.

On Friday, April 12th, around 3:30pm, we noticed a solitary, calling male, just north of the McGolrick Park pavilion.

We followed him, at a distance, to the protected lawns near Mr. Monitor. Indigos are tiny. Smaller than photographs and field guides lead you to believe. He flitted up to a London plane.

Migrating birds travel at night, navigating by stars. He came to us from southern Florida or the Caribbean or Mexico or even northern Colombia. He made it so far. He made it to our park. He was exhausted, we supposed.

His call, electric in quality, echoed—after alerting others to his presence via text, or even blinking—the startling effect of noticing him again. Improbable blues in the finally warming light.

We watched him and we listened, awestruck. It’s surreal to notice something so brilliant among passersby who don’t. Almost maddening. For unknowable reasons, he darted towards Monitor Street.

Many birds visit Monitor’s Willow Oaks. These trees, so close to apartments, can make the punkest birdwatchers self-conscious. You look suspicious peering through binoculars towards people’s homes.

Indigo Buntings are so blue that binoculars weren’t necessary. The naked eye was enough. The Indigo wasn’t flying for a Willow Oak. He saw something else. Something in, or behind, an apartment’s window.

He didn’t know what he saw. His species is older than humankind, as old as dinosaurs, certainly older than glass. Perhaps it was his first northbound migration. Perhaps some fractal of inherited wisdom sensed fecund wetlands, the once quiet fishing territory of the Keskachauge Lenape, not our stale patchwork of dirt and lawn, nor the strange cliff dwellings that surround them.

Your correspondent watched him silently touch a window then drop.

We found him on a stoop, frozen in his last moment. After making it at least a thousand miles, his journey ended at 155 Monitor Street. Mercifully, the death was quick.

Every year one billion birds fatally collide with glass in the U.S. alone. 155 Monitor Street isn’t some modern, phallic, glass behemoth. It’s a classic Brooklyn three-story building with old windows.

Spring migration is an exhilarating time for birdwatchers. The sudden presence of long-absent bird species awakens dormant fervors. Determined, gear-addled birders clunk around “hotspots” like junkies, loud-whispering names of birds they’ve either “got” or addict-scritchy-scratch “need”. They line up like paparazzi. They compare their checklist counts to competitors’. They ego trip. They call coveted species who don’t appear for them nemeses. Our Indigo lays bare the absurdity of all this.

He also leaves us with anger, hope and gratitude. Anger at human ignorance that threatens the ancient cycles. Hope that a growing awareness among next generations can shape future cityscapes more attuned to nature. Gratitude for the lesson that in the Anthropocene, when being a wild animal is perilous, _every migrating bird is a miracle_.

He was the first Indigo in modern history recorded in McGolrick Park. There may some day be another. For now: Indigo, thank you for your lesson. Fly well beyond the glass.

McGolrick Bird Club will bury him in our park, on a date and in a spot that feel right.