Happy almost February, Friends!

For all you bird-curious readers out there, this edition of The Noticer’s Monthly features our (self-proclaimed) definitive guide: How to Do Birding. Whether you’re a burgeoning birder or a never-tried novice: READ ON.

Also, if you like what we do, become a paid supporter of The Noticer’s Monthly. It’s because of oddbirds like you that we’re able to keep this cloacal media project thrumming, so thanks!

And welcome back. We’re very glad to see you.

MICROSEASON: JAN 13 - JAN 26

Unlike the parochial quarters of labor time made up by corporate humanoids, micro-seasons are straight from Source, the Great Unity, the god-babe herself: Mother Nature née Pachamama, Bhumi, Gaia, Demeter, Danu…

This micro-season, in McGolrick Park, our urban forest proxy for New York City, and perhaps even larger swathes of the wild eastern US, one noticed:

Gradient skies of blue, lavender and white · Perennial greens remain · First deep freeze · Fast moving Cirrocumulus clouds

As for McGolrick’s bird species, we noticed:

Peregrine Falcon · American Kestrel · Merlin · Dark-eyed Junco · White-throated Sparrow · Tufted Titmouse · White-breasted Nuthatch · Red-tailed Hawk · Cooper’s Hawk · Downy Woodpecker · Red-bellied Woodpecker · Northern Flicker · Yellow-bellied Sapsucker · Northern Cardinal · Blue Jay · Fish Crow · American Crow · Common Raven · Canada Goose (flyover) · Double-crested Cormorant (flyover) · Plus the virtually always present in urban parks: Rock Pigeon, European Starling, American Robin, House Sparrow and Mourning Dove

Japanese micro-season: Pheasants start to call; Butterburs bud

Ravens vs. American Crows! (Fish Crows emit caws that sound sinus infected)

Types of clouds

HOW TO DO BIRDING

One trembling hot summer day, after hosting an hours-long birding outing, your correspondent was sheepishly approached by a first time attendee who really seemed to get the day’s practice. “So, um, how do I learn birdwatching?” she asked. The question was as much a gut punch as an epiphany. “A primer is needed,” your correspondent concluded.

What is Birding?

There’s no shortage of uninspiring guides out there. They usually start with the same stale Webster’s stuff: “Birding is the act of experiencing and enjoying wild birds.”

WUGH. Sleep startled! Sorry.

These well-meaning writers make birding sound like a cute, passive hobby for people with too much time on their hands or an obsession for ticking species off lists.

Now, picture this: You’re a version of yourself long before glowing screens controlled your life. No phone, no noise, just you in some raw, vast, ancient landscape—endless savannah, fecund jungle, snowy river bank, etcetera. Your clothes aren’t poly-cotton; they're buckskin, woven from the land. Your scent isn’t D.S. & Durga, it’s rich, earthy dirt. No Twitter, no TikTok, no addiction to a never-ending vortex of social media outrage, narcissism and occasional meme humor, all propelled by an algorithm that idiot savants and rapacious bureaucrats haphazardly modify to keep you scrolling endlessly for their profit, force-feeding you thoughts and opinions and feelings you’d never naturally find on your own, in an epidemical and mass reshaping of human culture whereby the whole world is becoming humanoid, full of creatures who look human but aren’t! 😵💫…😮💨

Instead, your mind is focused, sharp and attuned to the smallest shifts in the world around you. This is a world where every shape, every sound matters. You're not just passing through—you’re in it. You’re hunting, you’re gathering, you’re surviving. Every move you make is careful and deliberate. There’s no room for the mental clutter of modern life—no status anxiety, no depression, no outrage—just the immediate, the real. The world is alive with meaning. Nature spirits sing. Earth gods smile. You are present. And in that presence, there’s peace, there’s gratitude, there’s awe—there’s reverence for the everyday sacred.

Sound distant? It’s not. When you go birding, you’re not just looking at birds. You’re tapping into this primal, ancient way of being. The heightened awareness, the sensory richness, it’s all still inside us, buried beneath the noise of our humanoid lives. By reconnecting with the natural world—by noticing birds—you can reclaim this lost self and its attendant meaning. Through birding, we learn to see the world, and ourselves, in ways we’ve almost forgotten.

Active Noticing

Practically speaking, birding is just going outside and turning your visual and auditory senses all the way up—entering a state that one might call active noticing.

On the D.L. Tip

First, try deep listening. That practice, as described by its creator, artist Pauline Oliveros, involves “listening in as many ways as possible to everything that can possibly be heard.”

Think about how you currently experience sound. What do you actually hear? For most modern humans, the answer is: not much. Though this may be adaptive—we subconsciously ignore non-crucial sensory input—we’ve gone too far, rendering our auditory awareness almost non-existent. Deep listening rewires that disconnected circuitry.

Go outside and listening intently—to everything. How do you know if you’re doing it “correctly”? It’ll feel different. So different that you may find yourself wondering, “How is it that I could have walked this place so many times, and not heard anything at all?”

Seeing's Believing a' the World o'er.

Second, try to really see (and not just look at) the world. To look is to merely enact your typical, autopilot-ish, subconscious scanning—enough to move around. To see is to let your vision fall back and settle into a conscious, sort of soft, wide-open focus that allows in as much information as possible.

How do you know if you’re actually seeing? First, you may notice that your visual field is surprisingly limited, à la the tunneler’s view in Being John Malkovich, and that to truly see, you must pat the world down with your eyes. Second, previously invisible dimensions of your everyday life will suddenly appear. Old brick buildings, unusual signage, Garry Winogrand worthy scenes of human primates sneering and smiling. These elements were of course always there, you just didn’t notice them.

Noticing Birds

A primary sign that you’re deep listening and seeing? Birds 👏 will 👏 be 👏 everywhere 👏. Downtown, austere desert, antarctic ice sheet: doesn’t matter. Aves are the only other animals, alongside homo stupidsprawlius, who’ve mastered every environment on earth.

Focus on the Breath Birds

But to notice birds well, especially the less common ones:

Place your attention on bushes, trees, building tops, and sky

Walk deliberately and lightly, as if to avoid pissing off the ground (h/t: Lil Wayne)

Pause for ear-catching sounds, movement, and anomalous shapes

Don’t strain, don’t overthink, don’t fret

Head yonder

Where outside should you be doing all this? Around your neighborhood is fine. If you live near a park, go there. The bigger, wilder and more watered the setting, the better.

And if you’re really keen on finding places birds like, plug your address into eBird.org then browse for “hotspots,” places with the most recorded sightings. (You can do this for any location in the world! Instructions below.)

Learning Names

As our human dominance of the world grows, so does our “species loneliness”, what philosophers call the state of alienation and disconnection—the deep, nebulous sadness caused by our estrangement from nonhuman lifeforms, from the loss of relationship with nature. Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of the canonical “Braiding Sweetgrass,” views naming as a mode of sacramental re-communion with the world.

In indigenous ways of knowing, all beings are recognized as non-human persons, and all have their own names. It is a sign of respect to call a being by its name, and a sign of disrespect to ignore it. Words and names are the ways we humans build relationships, not only with each other, but also with plants and animals. Intimate connection allows recognition in an all-too-often anonymous world… Intimacy gives us a different way of seeing.

Learning bird species’ names isn’t just the masturbatory purview of twitchers trying to impress one another. It’s a surprisingly deep, powerful practice of reconnection.

It’s Not That Hard

There are ~1000 identifiable bird species in the U.S. That’s a high number of anything to learn. So, for good reason, naming birds can seem overwhelming.

Take heart in these facts:

Those ~1000 species are distributed across North America’s vast landmass and myriad ecosystems, meaning as soon as you zoom into states, counties, towns, micro-climates, and seasons, that count drops to more manageable numbers*

Adaptive radiation, where many different bird species evolved from a single ancestor, means that if you learn one titmouse, like the Tufted Titmouse found in the eastern U.S., you’ve basically learned the titmouse look—small gray bird + handsome crest. As a result, the Bridled, Oak, Juniper and Black-crested Titmice will be that much easier to name

Wherever you are, your first encounters will be with the small number of bird species hyper-common to human settlements, such as the European Starling, American Robin, House Sparrow, Mourning Dove, Northern Mockingbird and Rock Pigeon; and less common but abundant species, like the Red-tailed Hawk, American Crow and Downy Woodpecker. These birds are your foundation—the base layer on top of which your skills and understanding will accelerate. The Downward Dogs to your eventual Lotus and Scorpion Poses

Repetition, repetition, repetition

The real secret to learning names isn’t study, it’s repetition. Your correspondent shouldn’t be the first one to tell you this, but everything good in life comes from repeated practice, even if it’s just a few minutes a day. Self-improvement, mastery, dream fulfillment, personal growth—fill your buckets, drop by drippy drop, friend.

Our recommendation: allot 15 minutes a day to birding. Try to go before or after work.

Tool Time

The greatest tool in the universe is your beautiful, squishy brain. The second greatest is a good pair of binoculars.*

Tied for a distant third: two non-evil phone apps that are great in-field learning aids. (Just make sure that while using them, your phone is in airplane mode, lest your attention get sucked away from the numinous moment.)

iNaturalist. This app’s Photo ID tool suggests species names for birds you manage to photograph.** Plus, once you submit your sighting, an unseen crowd of helpful folks will verify, correct and oftentimes explain their review. (Zoomed-in and blurry photos are usually okay! Feature works on plants and other animals too!) [iOS, android]

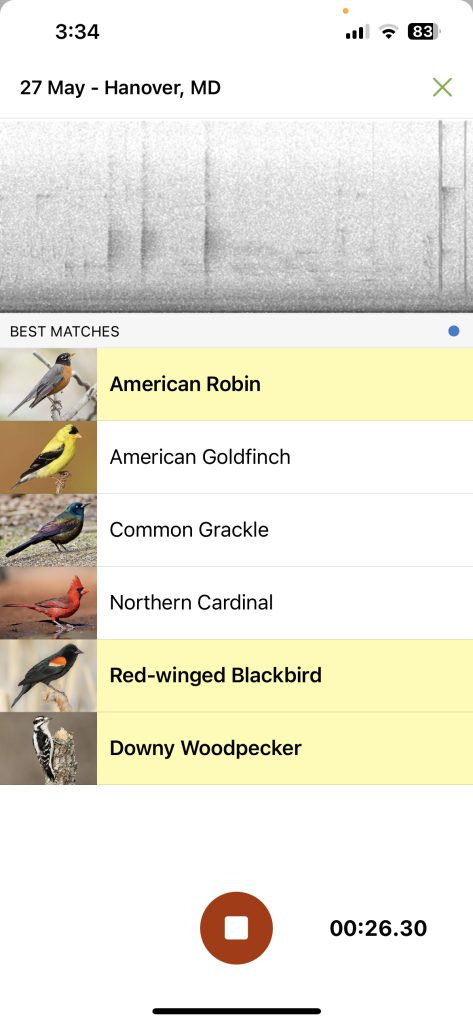

The Merlin app has a great Sound ID feature—think Shazam for birdsong [iOS, android]

You won’t be able to identify every bird you notice. You won’t always get the perfect look, clear view, decipherable photo or sustained, Shazamable birdsong. That’s okay. Learn who you can. Let the rest go. They were not meant for you. Bow to the great mystery and its lessons in humility.

*All you really need to learn birds is a good pair of binoculars—Audubon’s purchasing guide here—and an okay brain. When you encounter a bird, try your best to memorize things like its size, colors, eye-catching markings, length of tail, sounds, and behavior

**This kind of computer vision is also available within iPhone photos themselves, via a bird icon that auto-generates underneath photos featuring them, as detected by Apple. We’ve found the quality of Apple’s suggestions to be less accurate than iNaturalist’s

Getting Sparked

We don’t want to overstate anything, but by performing the repeating practice of—

going outside for 15 minutes a day

deep listening + seeing your surroundings

noticing birds

attempting to name them

—you will set in motion a mysterious but infallible sequence of events that leads to a preternatural reality, a sudden vision of the sacred, a flash of the eternal, a glimpse of a whole you can’t yet fully articulate…

More concretely, you will find your spark bird. What’s a spark bird? It’s the bird that catches your attention in an unexpected way, sparking an indescribable and immediate connection to the avian world. The spark bird metaphorically grabs you, shifts your perspective, and musters invisible psychic forces that support and sustain your journey toward learning, inspiration, energy, and yourself.

Final Thoughts

Birding is more than just looking at birds. It’s a way of changing your mind, of sharpening your animal senses in order to cut through your phone’s humanoid distractions and reconnect with the real, the immediate, the moment.

Because virtual noise is addictive, the simple practice of noticing then naming birds becomes a small but profound act of resistance and strength. Practice focusing your mind like you would playing an instrument; the more you tune, the more effortless it all becomes. Patterns emerge, connections form, and things that once felt random and chaotic suddenly make sense.

So, um, how do you learn birdwatching? Just go outside and pay attention, and rediscover the vast, mysterious, and very real world right in front of you. In the process, you’ll not only start to see beautiful birds—you’ll start to see the world, and yourself, more clearly.

Index, More Tools, Etcetera

iNaturalist’s Photo ID tool suggests species names based on a user’s photo(s). [iOS, android]

Photo ID is now built into iPhone Photos themselves, via a bird icon that auto-generates underneath photos featuring them, as detected by Apple. (We’ve found the quality of Apple’s suggestions to be less accurate than iNaturalist’s.)

Merlin has Sound ID, or Shazam for birdsong, and Explore: the easiest way to quickly learn what species are findable given a location/date, ordered from most common to rare. [iOS, android]

Instead of online news’s 24/7 horrors, browse eBird.org. While you can learn about bird activity at hotspots anywhere in the world, check those close to home, or where you’ll spend the most time birding. The recent observations and year-round likelihood charts are great for beginners.

Buy a field guide and browse it in your downtime, when you’re pooping, whenever. You might read up on species you just encountered. Or just let your curiosity guide you: What’s the most beautiful bird you can find? How many phoebe species are findable in the U.S.? What’s the difference between a Black-throated Blue Warbler and a Black-throated Green Warbler? What do the orange vs. blue vs. purple splotches within range maps mean?

Sign-up for rare bird alerts in your area. Chase one.